In Search of Taiping Houkui

Posted by So-Han on Jun 4th 2021

Taiping Houkui 太平猴魁 is an enigmatic tea. From its unusual name, which roughly translates to "Great Peace Monkey Chief", to its prodigious leaf size, distinctive shape and extreme rarity, it is one of the most eccentric of China's famous green teas. This curious and exquisite tea rose to prominence in 1915 when it won a gold medal at the World's Fair in Panama. Like many of China's celebrity teas - Longjing, Tie Guan Yin, Da Hong Pao - its notoriety is a double-edged sword: high demand and name recognition have led to an abundance of counterfeits. A search through a Chinese tea market is unlikely to turn up a single example of authentic Taiping Houkui, and when one does find the genuine article, it is almost invariably produced with modern techniques, the original methods having been lost for decades. So we set out in search of the elusive Monkey Chief in its homeland.

Authentic Taiping Houkui must be produced in a limited geographical region in the environs of Hou Keng Village in the Huangshan mountains of Anhui using a specific cultivar called Shi Da Zhong, "Big As a Persimmon", referring to the size of the leaves - it is the largest-leafed green tea in China, rivaling the Big Leaf tea plants of Yunnan used to make pu er.

In 2017 I was in Jingdezhen, adjacent to Anhui province, visiting my friend Mary Cotterman, then an artist-in-residence at the famous Sanbao ceramics studio. When I asked Sanbao founder Jackson Li about Taiping Houkui he connected me with Huangshan tea master He Xiaoling. Along with Mary, Montsho, and our friends Tran and Caleb (who took most of these photos), we made our way to Huangshan, meeting He Xiaoling in the famous Hou Keng village.

He Xiaoling originally hails from Sichuan province and has worked on various tea operations throughout China. Around 2012 she became fascinated with the legendary gold medal-winning green tea Taiping Houkui. In her own words, she wanted to taste the same tea that won that gold medal more than a century ago - not a modern approximation. The traditional processing technique is incredibly painstaking and expensive, and had been entirely replaced in the late 1990's by a faster, more efficient modern method. She set about to recreate the traditional style by referring to old tea processing manuals, video documentation, and by seeking out old tea masters who remember the technique. Taiping Houkui can only be harvested for a few weeks out of each year, and it took her three years of trial and error to successfully recreate the traditional technique.

I referred to counterfeit Taiping Houkui at the beginning of this article. The majority of what is found in the open market falls under this category, and it can be easily spotted. Made from ordinary green tea leaves pressed to be flat, straight, and paper-thin, the length of the leaves is artificially increased by rolling to make them appear long like the Shi Da Zhong variety. The result has an exaggerated length, a texture similar to toasted nori, and is translucent. It is generally light green and inexpensive. Such tea is not, in fact, Taiping Houkui at all.

This brings us to real, modern-style Taiping Houkui. Before ascending the mountain, He Xiaoling took us to a workshop where they produce genuine Taiping Houkui. One of the main features of Taiping Houkui is its long leaves, and a primary goal of its processing is to showcase this length by drying the leaves flat so that they don't curl up. In the modern processed, this is achieved by pressing flattened, freshly-cooked Shi Da Zhong leaves between sheets of fabric using a roller. He Xiaoling invited us to feel the fabric, which was wet from the juice of the leaves being crushed by the roller. She would later explain that this is where the modern process loses to the traditional one - the juice being squeezed out of the leaves is, in fact, the content of the tea - when the finished leaves are rehydrated, it is this juice that becomes the flavor and fragrance of the resulting beverage. The aggressive pressing technique produces a very straight, flat leaf, but sacrifices the quality and potency of the tea itself.

After this rolling process, the leaves are laid, one-at-a-time, between mesh screens that hold the leaf flat. These screens are slid into a rack - similar to the rack in an oven - over a brazier of burning charcoal to dry. After an hour or so, the bottom rack is removed and slid into another rack just above, with a continuous column of racks of leaves in different states of completion gradually making their way further and further from the charcoal. After 5 hours or so, the tea has made its way to the top rack and is completely dry.

This modern process results in straight, flat leaves that have distinctive grid lines from the mesh screen. In recent years, these grid lines have come to be recognized as a diagnostic factor distinguishing real from fake Taiping Houkui, but, ironically, the most traditional Taiping Houkui lacks the grid lines entirely.

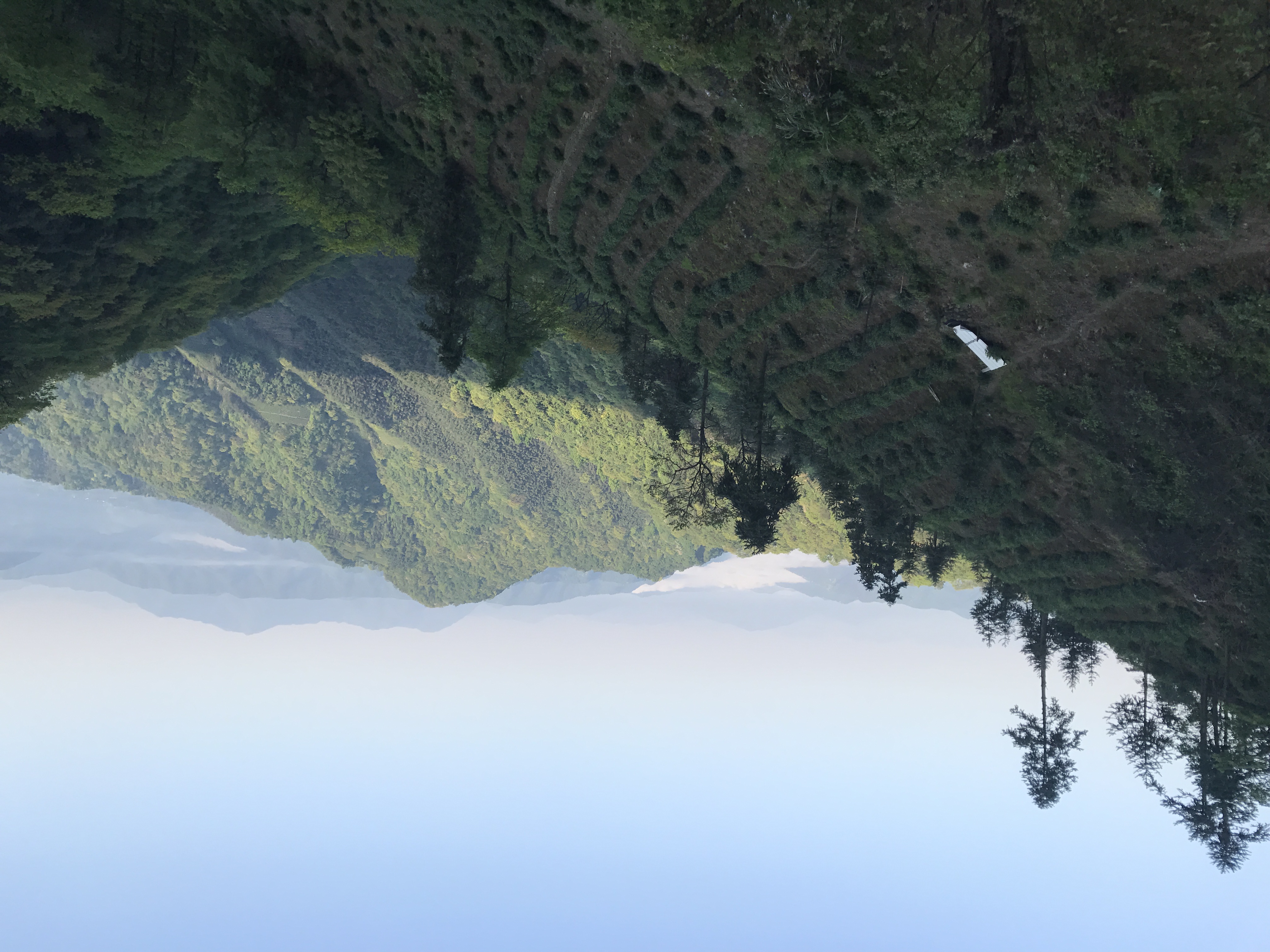

After visiting the modern Taiping Houkui workshop, we left He's vehicle in town and began the nearly hour-long hike to the ephemeral village of Hougang at the top of the mountain. This small collection of simple dwellings and tea processing workshops is vacant for most of the year, springing to life for a few weeks every spring for the brief Taiping Houkui harvest season. While it has power, it lacks running water, flushing toilets, and road access, and can only be reached on foot.

Like many famous tea-producing regions, the Huangshan mountains are strikingly beautiful, so much so that a school of classical Chinese painting is named after them

He Xiaoling guided us through the fields where she harvests her tea, distinguishing the Yin (shaded) and Yang (sunny) patches - the Yin patches are considered superior - as well as a meadow filled with wild tea plants. Ultimately, she told us, it was her intention to begin making different grades by separating different patches, as well as producing wild Taiping Houkui.

Once picked, the traditional process begins the same way that the modern process does - with a high-heat Sha Qing in a wok. The freshly-cooked leaves are laid onto a woven bamboo tray while they are still hot and soft, straightened by hand, and the stem is delicately crushed with the thumb. The tray fits like a lid on top of a large bamboo basket, wherein is contained a brazier of hot white charcoal. The leaves are sparsely distributed - roughly 150-200 leaves per tray - to allow them to dry evenly. When the master (He Xiaoling) has decided that the leaves are ready to move onto the next treatment, the tray is lifted off and moved to another basket containing another brazier of slightly cooler charcoal. There are three treatments overall that the leaves will pass through, at temperatures of roughly 90C, 80C, and 70C. Workers periodically check the various batches and restraighten them where they are curling.

By the end of the treatment, the leaves are fully dry, and they are piled into a woven tray to rest overnight. The dry, brittle leaves are rehydrated overnight from moisture retained in the stems. In the morning, the softened leaves are placed in a deep layer onto a tray over a final low-temperature charcoal treatment to dry completely.

The whole process is hypnotic. Clusters of craftspeople sit around giant baskets radiating heat and the intoxicating perfume of hot tea leaves. The work is precisely timed: from the wok to the trays, deft hands must operate without any wasted motion to get the leaves straightened while they are still warm and pliable. The queue of trays proceeds like clockwork, with the coordinated effort of a whole team of people gently moving each tray to the next basket without disturbing the leaves. We had the opportunity to assist in this process - the patient, methodical work of straightening and placing every leaf before gently crushing the stem into the bamboo was meditative.

The finished tea feels heavy with the weight of the effort put into each leaf. The flavor can only be described as deep, bright, and green, something like the smell of pine trees, but as a taste. The infusion is green and clear like a forest pond. The fragrance is a core of rich vegetal notes with a fanfare of complex floral bouquet. Overall, the tea tastes, smells, and feels extremely green and plant-like - a broad, generalized plantiness, like walking through a greenhouse or a jungle.

The leaves are long, but neither completely flat nor straight, and they lack the grid lines associated with the modern process. She calls this tea Gu Fa (古法, meaning "Ancient Technique") Taiping Houkui, to distinguish it from the modern method.

Essentially the difference between the processing styles is this: by initially pressing the leaves flat and then setting them between two screens, the modern method is able to reduce the time from 24+ hours to around 5 hours, reduce the amount of charcoal used by treating multiple stages with a single brazier and simply moving the tea further away to achieve less heat, and reduce the personal by roughly a factor of six. The efficiency gain is immense, which explains why the traditional method had essentially gone extinct. Furthermore, the aesthetic appeal of the modern method, with its sheaf of perfectly straight leaves, is undeniable.

Equally undeniable is the impact that this shortcut process has on the final quality of the tea. When compared side-by-side with same leaves processed in the modern fashion, the volume, complexity, longevity, potency, and depth of the tea is magnified. The juice squeezed out of the leaves by the roller is the substance of the tea, and its absence from the flattened leaves is glaring. It's almost as though, side by side, it feels like fewer leaves are present in an equal-sized dosage of the modern-processed leaves. There is essentially less tea per gram of leaf.

Equally undeniable is the impact that this shortcut process has on the final quality of the tea. When compared side-by-side with same leaves processed in the modern fashion, the volume, complexity, longevity, potency, and depth of the tea is magnified. The juice squeezed out of the leaves by the roller is the substance of the tea, and its absence from the flattened leaves is glaring. It's almost as though, side by side, it feels like fewer leaves are present in an equal-sized dosage of the modern-processed leaves. There is essentially less tea per gram of leaf.

I am in the habit of adopting, as my serving technique for a given tea, the method used by the people who produce the tea. In Hougang village the masters, farmers, craftspeople and technicians all serve Taiping Houkui in a tall glass, similar to the way Longjing is prepared in Hangzhou. Not only does this allow the tall, beautiful leaves to be seen in all their splendor, but the open glass vessel quickly cools the water, which allows boiling water to be used. The hot water appears to be necessary to get the large leaves to open.

This tea represents, for me, one of the most moving and endearing aspects of tea culture, which is the skill, patience, commitment and dedication that tea farmers, masters, and craftspeople put into their work. The amount of effort that goes into picking, cooking, and drying leaves goes beyond the monetary incentive of making a product to sell. Arguably, more money is to be made making the modern style of, or even counterfeit, Taiping Houkui. Rather than being an immediate selling point, this labor-, time-, and resource-intensive process must be defended again and again, the absence of gridlines explained, the high cost justified. It is only through the passion of He Xiaoling and her team that this remarkable process, and the sublime tea it produces, can exist.

How You Can Try This Tea

We are honored and fortunate to have access to this Gu Fa Taiping Houkui and be able to sell it. Each year the entire harvest sells out within a few weeks of harvest, so we reserve as much as we can. Selling this tea, like producing it, is a labor of love and a financial liability. We do our best to pre-sell the majority of what we order. This tea is many times more expensive than most teas available in the West, but sharing Chinese tea culture in all its expressions, and to the greatest degree of accomplishment and refinement as we have access to, is our mission.

This year, for the first time, we were also able to acquire a small amount of the wild Taiping Houkui that He Xiaoling alluded to years ago. While not made from the clonal Shi Da Zhong cultivar, it does feature equally-long leaves, as the wild tea plants are related to Shi Da Zhong, but are seed-propagated. Because it is so limited in quantity, we are initially making this tea available to member's only, and will release it to the general public after member's have had first refusal.

Photos by Caleb Bryant Miller and So-Han Fan